Tim Ainsworth is Executive Director of Brand Experience at McCann Manchester and NDA’s new monthly columnist. This month’s column was co-authored by Hannah Ainsworth, Brand Experience Integration Director, McCann Manchester.

I am old enough to remember the days when a shiny new tool called econometrics, a groundbreaking measurement solution in its day, hit the market and revolutionised the way we thought and felt about attribution.

Although powerful, its opacity often resulted in clients becoming suspicious of a so-called “black box” powering the decisions that could ultimately determine the allocations of £millions of marketing investment.

As an ardent advocate of the highly-skilled practitioners in marketing mix modelling, it’s a travesty that – perhaps (partly) as a consequence, but arguably born more of the birth of “performance” as a discipline – attribution models have paradoxically run amock with less degrees of control for clients over – and understanding of what is happening – the closer you get to the engine room of clicks and conversions.

That’s a problem for a number of reasons:

1. It is largely acknowledged that attribution models don’t paint an accurate picture of the full cause and effect of the full marketing ecosystem.

2. Clients are reporting spiralling compound YOY costs on their paid search investments, which is becoming about as controllable as energy costs.

3. The performance of that investment can range wildly, resulting in dramatic rises and falls in predicted baseline revenue performance.

This is not just stymieing growth: it is fast becoming an existential crisis for brands.

In paid search, particularly, what was once determined by technical prowess – largely governed by the awesomeness of the practitioner driving it – boasting “transparent” analytics and a clear path to attribution has become the blackest of black boxes.

And so it follows, the steady march of online marketing methodologies towards fully AI-led decisioning has presented ecommerce businesses in particular with a challenge: how do you win in rules-based media environments when the rules are the same for everyone but the platforms keep changing them without telling anyone?

What are we talking about when we talk about AI-led decisioning in the context of Digital Marketing?

Platforms like Google Ads and Meta now place your ad spend where their algorithm determines you’ll gain the most value back for your investment. Depending on the platform you’re using, it’s called different things: smart bidding, programmatic buying, pMax and automated ads would all be examples of this.

Over the past 5 years, marketeers have seen a seismic shift in our industry towards these fully-automated methodologies. For paid search SMEs specifically, It started with the introduction of features, which purported to be able to make strategic up and down weights to your maximum costs per click based on “signals” which allowed the algorithms to predict how likely someone was to convert based on things like past behaviour, time of day, search history etc.

Then, gradually, the manual features we could use to make decisions ourselves – or the data used to make those decisions – started disappearing from the platform. Now in 2024, the majority of the manual leavers we used to pull as PPC professionals to optimise the efficiency of an account have, sadly, vanished.

Winning and losing in the search landscape is largely now driven by the algorithm and not by the people managing the accounts. Higher click-through rates signals to the algorithm that your brand is worthy of more visibility and thus, just by virtue of being a bigger brand with stronger brand awareness, your ability to attract the click can multiply by factors of hundreds.

Algorithmically-controlled bidding has meant PPC went from being a meritocratic platform – where best practice led to great results – to an engine: where it seems the algorithm automatically gives visibility to brands mostly likely to attract the click, which in most cases are brands with higher brand awareness. Brands who have grown via ecommerce suddenly find themselves spending more to get less in a perpetual cycle.

The challenge of Performance Max

If smart bidding and the birth of machine learning in Google Ads was the start of this journey towards full automation, then Performance Max campaigns are only a few steps before the destination. It’s a fully-automated campaign type that can place your ads across any Google property (Google shopping, search, display, Gmail, YouTube, apps etc) and there is no significant manual control over where your ads appear, who to and at what cost. Everything from the amount you bid for a click to the ad copy that appears is generated and optimised by Google.

If you’re an ecommerce business that’s been heavily invested in scaling performance marketing through Google Ads, you’re likely invested into pMax campaigns and you might have noticed a gradual decline in the efficiency of your marketing efforts over time. Brushing it off as “standard Google inflation” or “increased competition” – although perhaps true – can be a dangerous game. If your business cannot pull spend away from an ever-increasingly-expensive channel without compromising performance, that’s a problem, no matter what the channel happens to be.

Two simple metrics can be used as an early warning system:

a) Media Efficiency Ratio (MER)

This is your total revenue divided by your total ad spend across all channels. If you see your search spend increases but your MER decreases at the same time, this is a red flag.

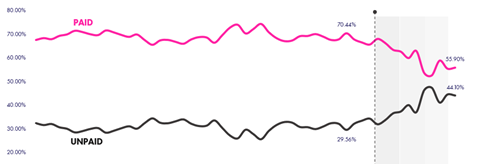

b) Paid Session %

This is simply the percentage of sessions on your website that came from paid channels versus unpaid channels. Always include brand search volumes (either PPC or SEO) as unpaid traffic as users use Google as a front door to your website (often). If your paid session % is above 60%, this is an imbalance.

If you’ve just run the diagnostics above and discovered a result you’d rather not have, you’re probably in good company from hundreds of other ecomm businesses who find themselves equally over-reliant on buying traffic.

How we got here as an industry is interesting. When pMax launched, marketers were seeing massive increases in revenue and efficiencies attributed to their new pMax campaigns. The pervasiveness of this attribution fallacy led to a 41% growth in Google’s revenue in a single year – the largest single year growth in years.

It’s easy to see though how brands ended up so heavily invested: when Performance Max launched, the campaigns were an almost perfectly pitch-black black box, with no ability to report on keywords, ad copy performance or even which of Google’s inventories your ads were serving on. The lack of data was one thing but a moot point, because we can exert little to no manual control over these factors anyway within the campaign settings.

So, why would that matter if the activity was running efficiently? Afterall, pMax does allow you to set a level of efficiency for the campaign that you’re comfortable with. It’s how the algorithm achieved that efficiency that is at the heart of the challenge:

Targeting very warm traffic

Attempting to steer the algorithm away from serving ads to existing customers or repeat visitors proved problematic with pMax. Serving ads to users who already intended to purchase essentially compelled businesses to pay for customers that could have been attracted for free, through SEO or direct channels later on. Industry feedback influenced Google to introduce a tick box for “new customers”.

However, the definition of a new customer appeared to be very loose. Given the brief lifespan of cookies on various browsers and devices, the tick box appeared futile. How this will behave once the (now again delayed) cookie depreciation happens is unknown.

The brand conundrum

During launch, pMax lacked the capability to exclude brand traffic from its activity. This posed a significant issue, as the algorithm bid aggressively for brand traffic due to its higher likelihood to convert efficiently. Audits revealed instances where the price of a brand click in a standard search campaign was £0.03, while the same traffic delivered through a pMax campaign skyrocketed to £2.30 per click.

In response to industry concerns, Google allowed the exclusion of brands (including competitors) from pMax campaigns; but, this pertained only to the pure brand term. If your brand name is frequently misspelled, the exclusion is less impactful.

Credit where credit is due

The in-platform attribution model for both GA4 and Google Ads claims to be data driven. However, we noticed that when pMax was activated in most accounts, the overall revenue remained unchanged or only marginally improved, but there was a sudden surge in revenue attributed to pMax compared to other channels. The anomaly raised eyebrows.

So, how do brands who recognise themselves in the above challenge emerge successfully?

Dependency on Google or any algorithmically controlled marketing platform is unsustainable and can result in escalating marketing costs long term. While PPC does a job creating physical availability very effectively, without mental availability it will never run as efficiently for you as it does for your competitor category leaders.

We cannot control the evolution of bidding platforms like Google Ads, nor the behaviour of the rest of the market in adopting more and more automation. What we can control is our own behaviour, and the way we view collective marketing effectiveness through the lens of nourishing channels like paid search, rather than relying on the channel itself for performance.

Focusing less on attribution as our measure of effectiveness and more on holistic KPIs cross-channel will help us to understand the true value of pMax in the round. Paradoxically, perhaps the answer to the PMax challenge is better MMM, which in turn takes us back to econometrics.

It’s possible to reduce your reliance on PPC and grow a sustainable Brand at the same time, the results achieved here took a matter of a few weeks:

Source: McCann Manchester: Brand Vibrancy Score, 2024.

There is light at the end of the tunnel for those who are willing to look left, right and up out of this landscape for growth (way) before the click.